Max Beckmann, Weather-vane from the series Day and Dream, 1946

Sydney Norton

Museum Educator and Coordinator of Public Programs, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Day and Dream is an enigmatic series of fifteen lithographs that Max Beckmann made in 1946, at the close of his nearly decade-long period of self-imposed exile from Nazi Germany in Amsterdam. He completed the portfolio on June 24, shortly before embarking on his long-awaited journey to the United States, where he would live and work until his death in 1950. The series deals specifically with themes that preoccupied the artist during his final years in Amsterdam. Revealing little of the scathing social commentary that characterized many of his prints from the 1920s,1 the subject matter of the Amsterdam lithographs is more private in nature, evoking, for example, feelings of entrapment and disorientation and allusions to life in Holland; his recurring concerns about war; and references to the artist’s hope and optimism about career prospects in the United States.2 While many of these lithographs are specific in terms of subject matter and place, others are more uncertain, reflecting on questions of morality and religion, which many scholars relate to his ambivalent relationship to Third Reich politics.3 The works are multilayered and speak on both literal and metaphorical levels, offering viewers striking yet ambiguous visual clues about the cultural disorientation, ethical dilemmas, and social influences that informed Beckmann’s life and self-perceptions during his time in Amsterdam after World War II.

The artist made Day and Dream upon request of Curt Valentin, the influential New York art dealer who emigrated from Berlin to New York in 1937. As an exile with connections to powerful art dealers in Nazi Germany, Valentin enjoyed the uncommon privilege of being allowed to purchase confiscated modern art from Nazi authorities for the New York gallery that he managed.4 Largely responsible for introducing Beckmann's paintings and other European modernist works by such artists as Fernand Léger, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Max Ernst to the American public, Valentin believed that producing multiples of a recent portfolio would further enhance the artist’s reputation with American collectors.5 He expressed his interest in commissioning a new portfolio in a letter to the artist dated March 8, 1946, and Beckmann accepted the offer enthusiastically: “I’m teeming with countless ideas,” he responded. “I could make a portfolio with biblical or mythological themes, a circus-theater-café series, or all of them mixed up into one.”6

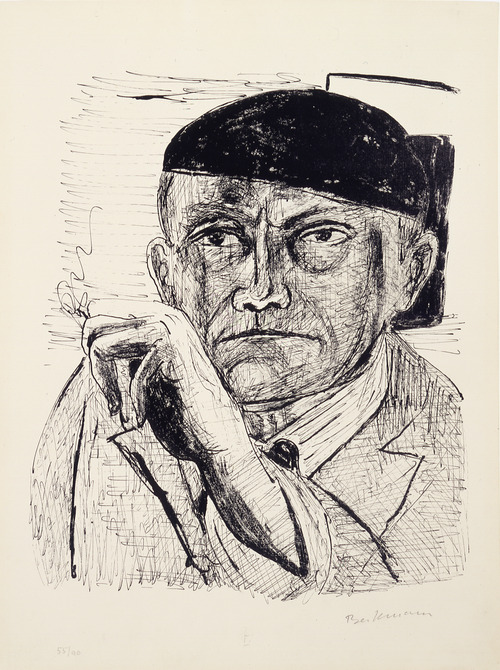

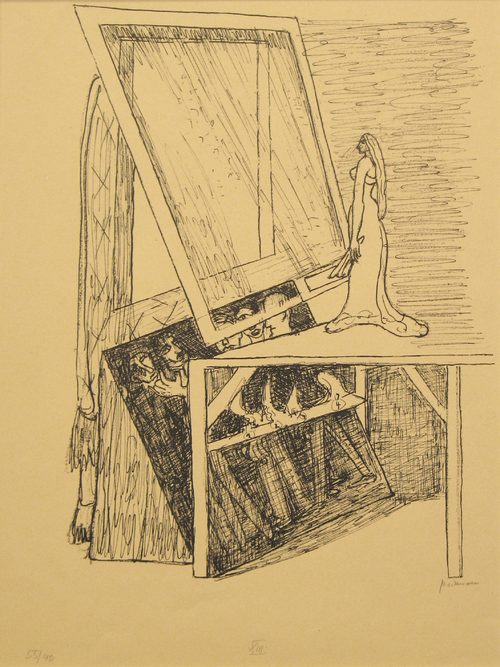

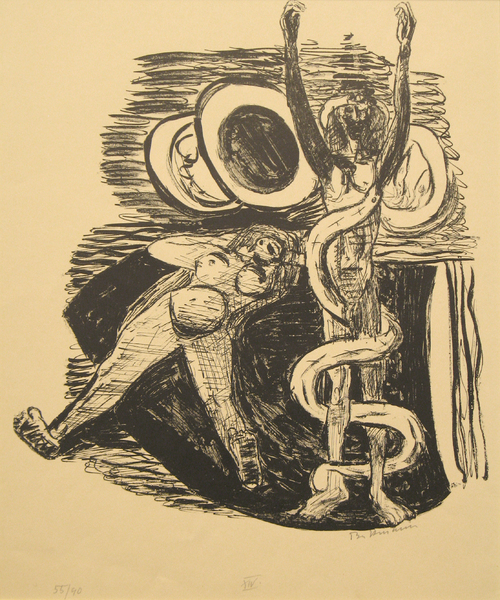

Beckmann decided upon the latter eclectic approach, and as if to underscore the portfolio’s diverse facets and impressions, he varied his drawing technique from plate to plate. In some cases he used a fine litho pen, as in Sleeping Athlete, creating clean and smoothly defined images. In others, such as Weather-vane and Circus, he worked exclusively with crayon, producing coarser drawings that on first glance appear simple and childlike, but that upon closer examination prove rich in metaphorical content. In several cases, such as in Self Portrait, Morning, and The Fall of Man, Beckmann applied large sections of ink on the stone, a practice that resulted in intense and aggressive blackened areas on the paper that dominate the composition.7

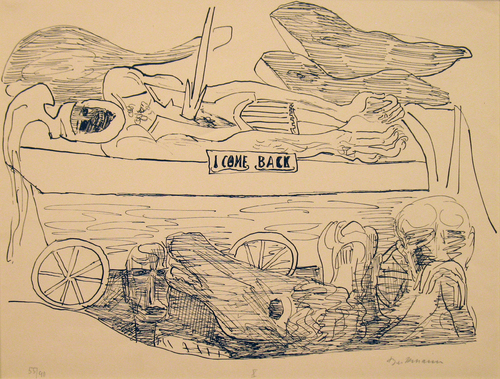

The varying techniques and themes that comprise the Amsterdam portfolio exhibit a lack of cohesion that renders an examination of the portfolio in a given sequence inconsequential. Resembling a collection of free-floating ruminations on diverse facets of the artist’s post-war circumstances, the prints can be viewed repeatedly and in a variety of combinations. Day and Dream, the portfolio’s title, underscores this apparent absence of a graspable linear development. The words evoke the daydream, a state of mind in which day (reality) and dream (imagination) are tied to one another, yet are removed from the logic of conscious thought and structured time. Beckmann’s original title choice, Time-Motion, a phrase still decipherable on a paper fragment in King and Demagogue, further suggests temporal and spatial ambiguity. Initially articulated in correspondence between the artist and Valentin, and again in Beckmann’s diary entry of June 24, 1946,8 Time-Motion conveys both a sense of passing time and transience, two phenomena that can be attributed to Beckmann’s experiences as an exile, for whom a feeling of perpetual waiting or arrested time becomes the norm.9 Both titles—Day and Dream and Time-Motion—serve as a foil to the viewer’s temporal and spatial expectations—one that is reinforced graphically through the artist’s frequent rejection of linear perspective, as in Sleeping Athlete and Circus; and alienated spatial and social configurations, as in Crawling Woman and The Fall of Man.

Further complicating matters, there are aspects of this portfolio that both Beckmann and Valentin developed for purely pragmatic reasons. Aware that ninety of the hundred portfolios printed would be shipped to the United States, both artist and dealer made choices for the suite that would appeal specifically to American collectors.10 The title appears in English, for example, and the cover image, published on linen, is a reproduction of Beckmann’s Globe and Shell, a 1927 drypoint etching that features a globe with North America as its focal point. Valentin selected this print, printed by Beckmann in Frankfurt twenty years before, as a means of visually referencing the artist’s future home and art market, a strategy that would help publicize to American patrons the artist’s intention of relocating to the United States.11

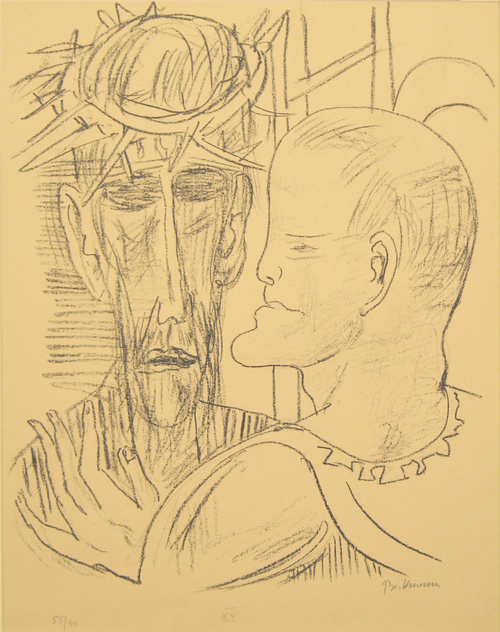

As is often the case in Beckmann’s print suites, the portfolio begins and ends with a self-portrait, a structuring device that provides nominal directive for the narrative dislocation that follows. These portraits contrast notably from one another, and offer substantial clues about the way the artist chose to project his public persona at a given time. In a sense, the opening figure serves as a charismatic master of ceremonies who invites the viewer to engage viscerally both with the projected image of the portfolio’s creator and with the dreamlike images that follow. Here, ubiquitous scribbles and crosshatching give form to an older man’s weathered, yet distinguished face. The artist’s rigid jaw-line accentuates an unsmiling demeanor that contributes to an overall countenance of serious resolve. His clothes—the beret-like cap, a jacket and shirt open at the collar—point toward a slightly bohemian figure, who is simultaneously grounded in the comforts of the bourgeoisie. Holding a lit cigarette confidently in his left hand, the artist radiates self-assurance and sovereignty. With his gaze fixed on a point beyond the viewer, he confronts the world head-on. Other self-portraits in the series are, in stark contrast, allegorical in nature. The final plate shows, for example, a profile of Pontius Pilate clad in ancient Roman attire, but whose facial features strongly resemble those of Beckmann. As a modern stand-in for Pilate, the artist has placed himself in visual confrontation with Christ, a dynamic that may allude to Beckmann’s and other Germans’ compromised ethical position in relation to Third Reich politics.

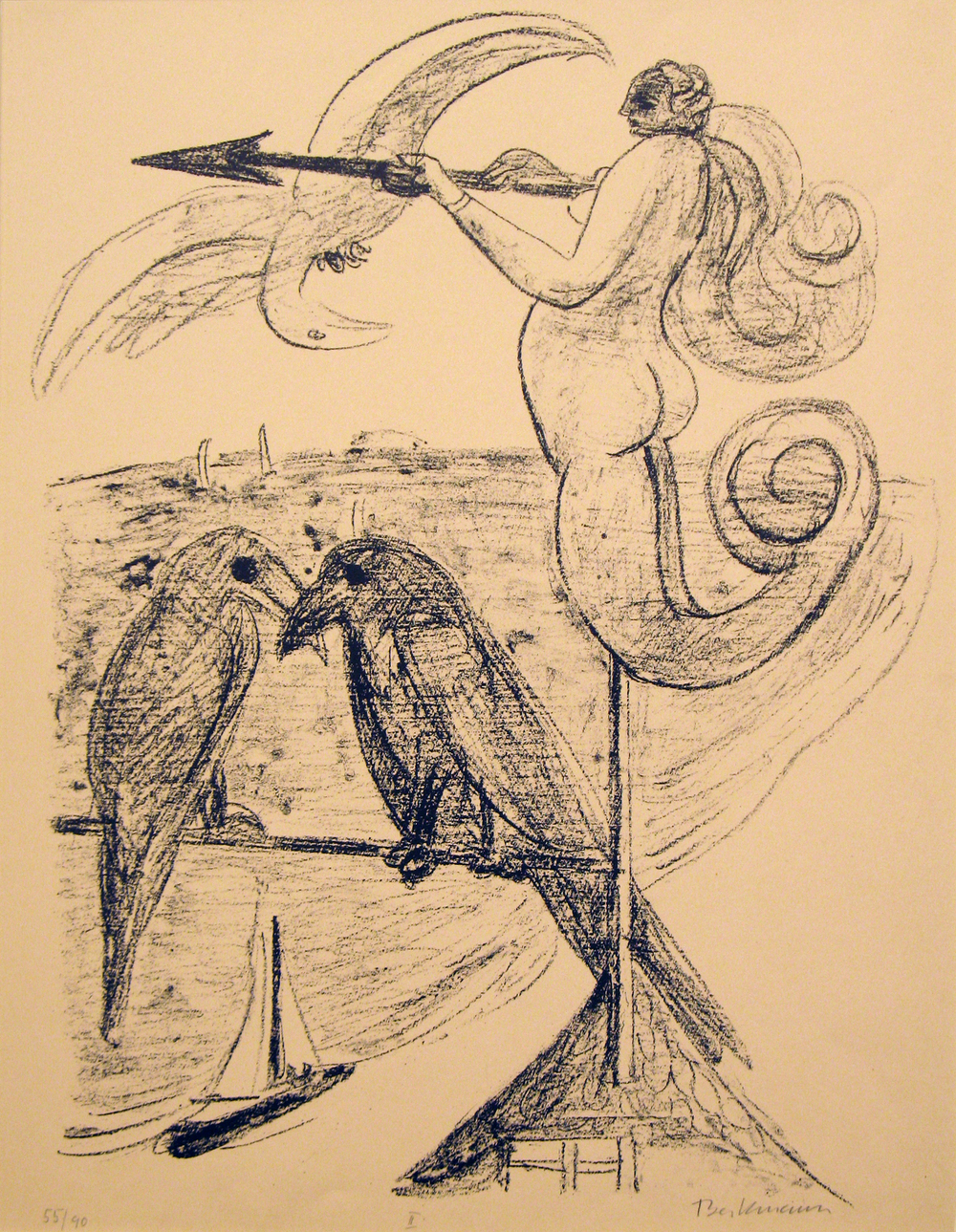

Some of the figures that comprise Day and Dream appear, at first glance, simple and larger than life, and for this reason, encourage precise iconographical readings. Yet these figures fluctuate, just as the title suggests, between the mundane and fantastical. The artist’s propensity to fuse the topical with the strange, combined with his tendency to disrupt the viewer’s narrative expectations through distorted perspective, make it difficult to arrive at definitive interpretations. Weather-vane of Day and Dream exemplifies this ambiguity. The lithograph features a rooftop weathervane shaped in the form of a mermaid holding an arrow that points toward the ocean. Tiny sailboats are visible in the distance. Two large black ravens are perched on a horizontal bar attached to the weathervane. Photographs taken from Beckmann’s window reveal that the artist saw a similar rooftop weathervane from his Amsterdam studio.12 This picturesque view likely served as a locus for the artist’s daily reflections and visualizations, while the composition, with its distant horizon line and harbor scene, more generally recalls the vast art historical tradition of Dutch seascape paintings.

The artist may have fused elements from two drawings in this print. In a diary entry dated March 28, 1946, Beckmann recorded the titles of two drawings he had just completed: “Frau mit Fischschwanz” (Woman with Fishtail) and “Pfeil und Raben” (Arrow and Raven), and it seems likely that these figures—the mermaid and the ravens perched on the weathervane—appear as one element here.13 This hybrid image placed within the greater context of a harbor invites rich and multifaceted readings. The fact that the wind directs the mermaid’s arrow seaward might reference Beckmann’s own much awaited journey, while the ravens, a foreboding omen in English and Central European folklore, possibly embody the artist’s fears about the future. A third bird resembling a seagull appears suspended in flight in almost direct opposition to the weathervane’s arrow. This lightly sketched avian form— visually at odds with rest of the composition—suggests a state of conflicted or arrested motion.14

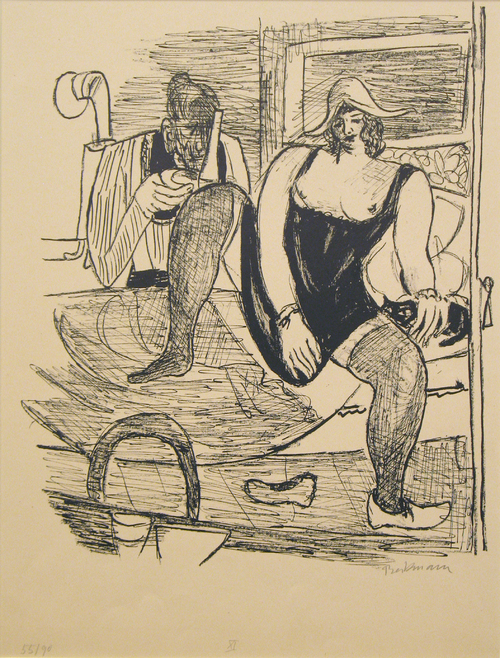

Within the context of Beckmann’s experiences as an exile in Amsterdam, several lithographs from Day and Dream reflect upon the connection between sexuality and human alienation. Morning, for example, is set in a sparse, cramped bedroom dominated by a large bed, head board, and heating pipe. At the center of the print is an image of a large, highly sexualized young woman. Seated on the bed with her legs parted in the direction of the viewer, she wears a negligee, which, due to its substantial size and massive concentration of black ink, is the focal point of the picture. The woman, possibly a prostitute, wears a Dutch cap and clogs, a clear reference to Beckmann’s host country. Leaning casually against a pile of pillows she strokes a black cat, a recurring motif in Beckmann’s oeuvre that is frequently associated with female sexuality.15 She has placed her right hand over her crotch in a modest gesture that seems to contradict her otherwise exhibitionist posture.

A puzzling figure kneeling in the background introduces a further element of uncertainty into the composition. Possessing both masculine and feminine characteristics— the hands are bulky and shoulders broad, yet the hair is pulled back into a bun—this person is advanced in years. Clad in a formless, long-sleeved robe or dress, the figure is poised to offer the young woman a glass of water or wine. The left hand clutches a bottle, the slender form of which runs parallel to the lines of the young woman’s torso, taking on a phallic connotation. Is it the woman’s partner who is marginalized in the composition’s background? Or does this figure’s neutralizing presence and scrutinizing gaze convey a moral judgment about the woman’s openly sexual behavior?

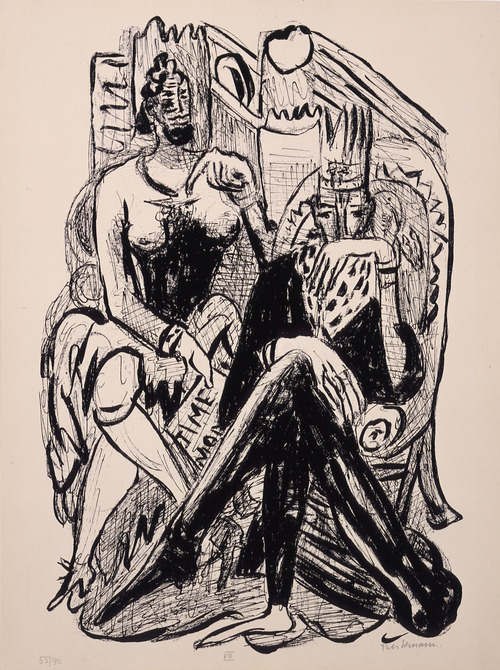

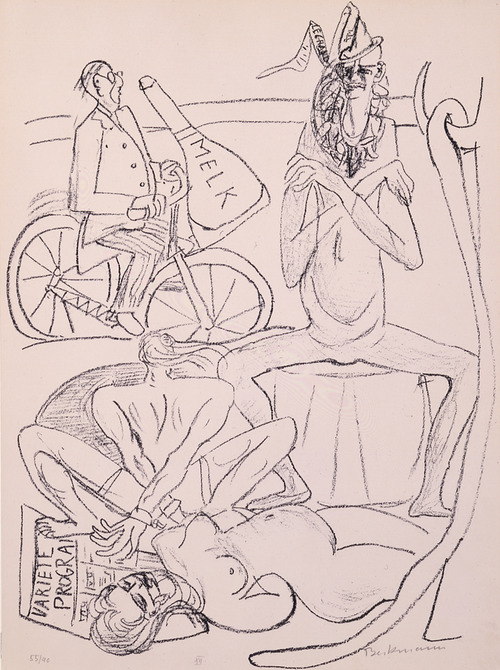

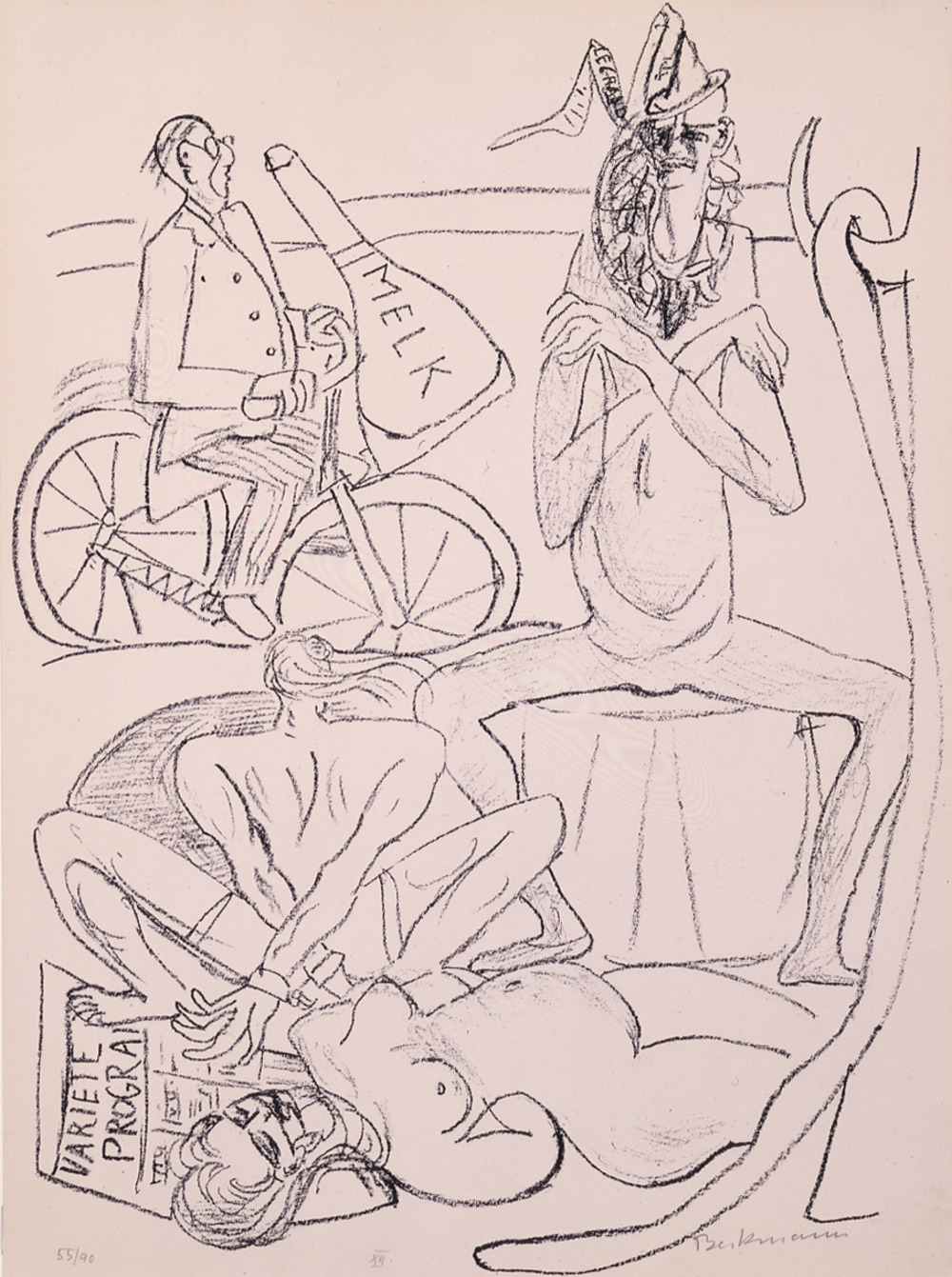

Other plates from Day and Dream reveal the artist’s recollections of everyday encounters with Amsterdam friends and acquaintances, as well as recapitulations of memorable shows by local circus and Varieté performers, spectacles that fascinated the artist throughout his life.16 Circus revisits subject matter from print portfolios and paintings made by Beckmann in Germany during the 1920s.17 In 1921, for example, the artist published Jahrmarkt (Annual Fair), a portfolio of ten drypoint etchings, focusing on circus performers— clowns, tall and strong men, acrobats, and tightrope walkers—both on stage and behind the scenes. In similar thematic vein, a clown and cyclist inhabit the space of the 1946 lithograph Circus, yet they are portrayed within the context of Beckmann’s Amsterdam experiences, and an air of violence permeates the scene.

In the right section of the print, the facial features of a tall, skinny jester wearing a clown’s hat recall those of the artist (as in the depiction of Pilate in the final plate). Crossing his arms over his chest, the man is seated with splayed legs on a drum or stool. Before him on the ground lies a nude woman with her arms tied behind her back and a cloth fastened around her mouth, a recurring image denoting captivity in Beckmann’s oeuvre.18 The muscular man crouching behind her, possibly her partner, wears only shorts and is also bound in handcuffs. On the ground beneath them is a variety show program, the existence of which presents captivity and physical torment—two commonplace forms of wartime subjugation—as a kind of a grotesque circus or variety show.

In a diary entry dated May 11, 1946, Beckmann referred to this lithograph as “Der Sieger,” or “The Victor,” and scribbled Zirkusszene (Circus Scene) in parentheses.19 Although “Der Sieger” is not listed as the title in the portfolio’s table of contents, the artist’s mention of the word in his diary helps shed light on this puzzling work. The victor quite possibly refers to the clown or Beckmann himself, who appears to survey the subjugation of his fellow humans in the foreground with a curious mixture of concern and critical detachment. Featured in the upper left section is a second figure, a bespectacled gentleman bicycle rider who hauls an oversized bottle of milk on his handlebars. Sources close to the artist have identified the bicyclist as the Beckmann’s milkman, who was imprisoned during the war for engaging in underground activities against the Nazis. Through Beckmann’s direct appeal to the Gestapo, the man was released unharmed.20 This momentous event appears to have served as a catalyst for the artist’s reflections on his personal role as a dubious victor or liberator in wartime Europe. While a definitive meaning of Circus remains elusive, Beckmann’s compelling juxtaposition of real and fictional characters takes us back to the portfolio’s overarching theme: the interchangeability between day (reality) and dream (illusion).

- 1 Max Beckmann produced 372 prints over his lifetime in the form of etchings, lithographs, and woodcuts. Spanning thirty-nine years of his artistic life, the majority of these prints were made in Frankfurt between 1915 and 1923, a period of extreme political and social upheaval. This tumultuous time, transformed by World War I and the political and economic unrest that followed, coincided with the artist’s most intense and creative phase in printmaking. By 1925 Beckmann had abandoned printmaking, devoting his energies entirely to painting. But he returned briefly to the medium in the late 1940s while living in Amsterdam.

- 2 Beckmann makes reference to these and other preoccupations in diary entries and letters written during the postwar years. See Max Beckmann Tagebücher 1940–1950, ed. Erhard Göpel (Munich: Albert Langen, 1955). For reference to these reflections in context of the Day and Dream portfolio, see Max Beckmann Welt-Theater: Das graphische Werk 1901 bis 1946, eds. Jo-anne Birnie Danzker and Amélie Ziersch (Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 1993), 162. To view images of all fifteen lithographs in this portfolio, visit Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum’s collection online (http://www.kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu/collection/ search?keyword=day+and+dream).

- 3 Beckmann’s relationship with Nazi Germany was complicated. Despite the fact that the National Socialists officially regarded his art as “degenerate,” and although Beckmann left Germany (on his own accord), he continued to cultivate friendships with influential supporters of National Socialism, both before his departure and during his time in Amsterdam. For a particularly cogent account of this, see Barbara Buenger, “Antifascism or Autonomous Art: Max Beckmann in Paris, Amsterdam, and the United States, 1937–1950,” in Exiles and Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, ed. Stephanie Barron (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; New York: H. N. Abrams, 1997), 58–67.

- 4 Despite Valentin’s Jewish heritage and émigré status, the art dealer collaborated with Nazi authorities in order to purchase modern paintings confiscated from German museums and private collections. Before relocating to the United States, he had previously worked for the highly successful gallery owner Karl Buchholz, who later became a member of the Nazi party. The New York gallery that Valentin established belonged to Buchholz and was called the Buchholz Gallery until 1951, when Valentin himself became owner. It is this connection that enabled the art dealer to purchase modern paintings from the German government throughout the war.

- 5 Beckmann was not unknown to American art patrons. In 1931 the Museum of Modern Art in New York featured eight of his works in an exhibition of German art. J. B. Neumann, his former Berlin dealer who had relocated to New York in 1931, also promoted Beckmann in his Manhattan gallery. See Karen F. Beall, “Max Beckmann: Day and Dream” in Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 27, no. 1 (January 1970): 4.

- 6 “Ideen liegen massenhaft vor. Man könnte ein(e) Mappe mit biblischen oder mythologischen Motiven eine Circus und Theater und Café mappe [sic] oder auch alles zusammen machen.” Max Beckmann Briefe III, ed. Uwe Schneede (Munich: Piper Verlag, 1996), 116. English translation is my own.

- 7 Whereas the portfolio edition housed at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum contains no further embellishments, Beckmann applied pen, chalk, and brush to some others. In four cases he made watercolor additions, which, according to his diary, he found “unterhaltsam” (entertaining), yet ultimately “unfruchtbar” (unproductive). See diary entry, Tuesday, April 13, 1948, in Tagebücher, 260.

- 8 See Briefe III, 116; Tagebücher, 167.

- 9 See, for example, Beckmann’s Les Artistes mit Gemüse (Artists with Vegetable), completed in 1943, which captures a feeling of limbo or suspended time through the static postures of the four exiled artists and through the claustrophobic spatial proportions of the room they inhabit. For further discussion of suspended time in Day and Dream, see Max Beckmann Welt-Theater, 162.

- 10 The artist had one hundred sets of lithographs printed in Amsterdam, and he signed ninety of them before sending them to New York. The original drawings for Day and Dream are located at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. See Thomas Döring and Christian Lenz, Max Beckmann: Selbstbildnisse: Zeichnung und Druckgraphik (Heidelberg: Edition Braus, 2000), 298.

- 11 Ibid., 298.

- 12 See Mathilde Q. Beckmann, Mein Leben mit Max Beckmann (Munich: Piper Verlag, 1983), 128–129.

- 13 See Tagebücher, 158; see also Martin Papenbrock, “Max Beckmann’s ‘Day and Dream’: Exilerfahrung und Amerikasehnsucht,” in Kunst und Sozialgeschichte (Freiburg: Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft, 1995): 328–345, esp. 332.

- 14 It is clear from Beckmann’s diary entries as early as November 1945 that the artist intended to relocate to the United States, and he looked forward to this experience with both apprehension and excitement. Yet because he was a German citizen, he was viewed by the Allied governments with suspicion and was forbidden to travel to the US, despite the fact that the war was over. In order for him to receive his exit visa, he was expected to obtain a “Non Enemy Declaration” from the Dutch government. He waited for this document for nearly two years, living in a state of limbo, unable to move forward with his plans. It is this suspension of time, characterized by deep frustration and high hopes, that informs the Day and Dream portfolio. See diary entries, January 4, 1945; March 23, 1946; June 24, 1946; and July 29, 1947, in Tagebücher, 137; 146; 195; 199.

- 15 A domestic black cat appears in a few of Beckmann’s prints, and in all of these cases the animal appears to be connected with female sexuality. For select examples, see catalogue numbers 90, 96, and 174 in James Hofmaier, Max Beckmann: Catalogue Raisonné of His Prints, vol. 2. (Bern: Galerie Kornfeld, 1990).

- 16 Like Pablo Picasso, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and numerous other twentieth-century modern artists, Beckmann was intrigued by bohemian circus performers, whose outsider status allowed them to function, albeit meagerly, within a realm removed from bourgeois conventions.

- 17 See Jahrmarkt (Annual Fair) in Hofmaier, Catalogue raisonné, catalogue numbers 191 to 200. The artist continued to explore the circus theme in his triptych The Acrobats (1939) and Acrobat on Trapeze (1940). Both paintings and the print portfolio are part of the permanent collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

- 18 See, for example, Die Gefangenen (The Prisoners) (1910) in the collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

- 19 Tagebücher, 165.

- 20 See Mathilde Beckmann, Mein Leben, 31–33.