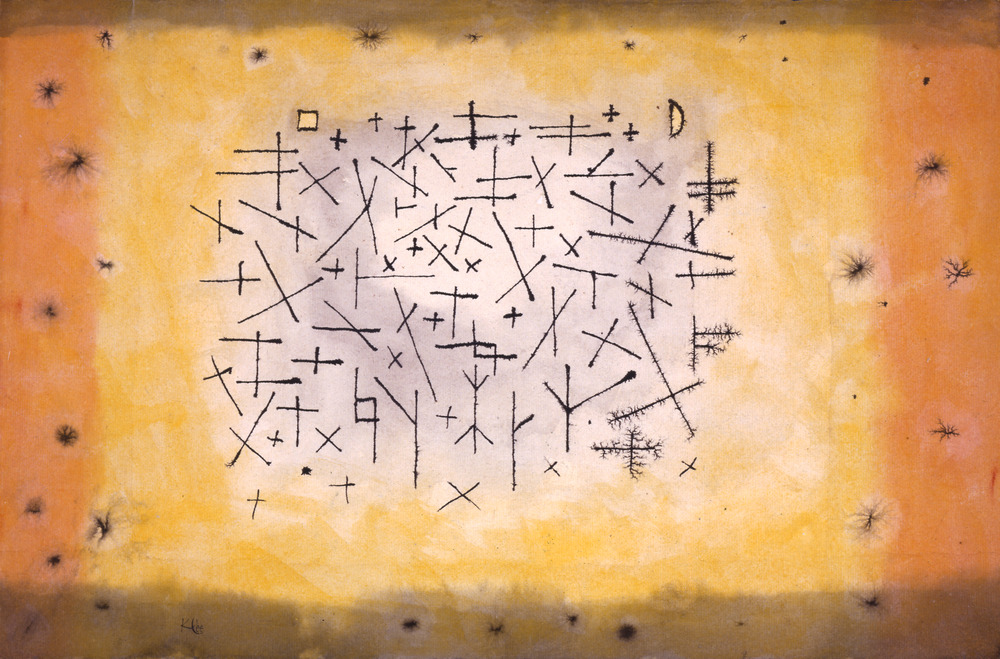

Paul Klee, Zeichensammlung Südlich (Collection of Southern Signs), 1924

Sarah McGavran

Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow, Department of Art History & Archaeology, Washington University in St. Louis

The title of the Swiss artist Paul Klee's Collection of Southern Signs (1924) alludes to the artist's travels south of Germany, his country of residence. This watercolor's aesthetics, however, evoke the arts of cultures subsumed under the concept of the "Orient," which in the early twentieth century encompassed the ancient and modern cultures of the Holy Land, North Africa, the Middle East, and Turkey. Klee first traveled to the so-called Orient as a young artist in the spring of 1914, when he went to Tunisia for two weeks with his artist friends August Macke and Louis Moilliet. Ten years later, the year he painted this work, Klee was an established professor at the Bauhaus, a school of applied arts in Germany. That same year, he took a second significant trip south, a six-week vacation in Southern Italy and Sicily. He later referred to the latter as the "springboard" to the "Orient."1 Nevertheless, the visual references in Collection of Southern Signs extend beyond the artist's direct experience of the "Orient" and of southern Europe. The signs at the center—especially the vertical line at the lower middle with three strokes at the top and bottom, and the horizontal crosses—allude to the Cuneiform script of ancient Babylon.2 As Europeans then considered the ancient Near East as part of the "Orient," these symbols are an immediate visual manifestation of Orientalism in the watercolor. In addition, the overall composition of a central medallion surrounded by a border recalls a common format of North African and Persian carpets. Klee was far from unique among modern artists in turning to "Oriental" and non-Western art to renew or inspire his own modern European painting, a practice art historians refer to as primitivism. Yet many of Klee's contemporaries were satisfied to stay in Europe and study these objects at ethnographic museums or at exhibitions. By contrast, Collection of Southern Signs suggests that Klee actually travelled in order to engage with non-Western art. That the title refers to a cardinal direction while the imagery relates visually to the arts of the so-called Orient suggests that travel away from Northern Europe, as opposed to a particular destination, allowed Klee to see new potential in the unfamiliar, or to read the signs, so to speak.

A closer look at Collection of Southern Signs helps draw out several themes that often surface in the artist's many works that relate to the so-called Orient, namely the ways different artistic media can inspire paintings and the relationship between the material and the spiritual. The namesake signs that resemble ancient and exotic writing are organized in a loosely circular group—instead of in registers like on a Babylonian clay tablet or in lines like words on a page—which renders them illegible as text. These forms hover in an atmosphere of shimmering silver and gold, as if to suggest a message written in the stars. A half-moon shape at the top of these cryptic forms reinforces the impression of a celestial subject. However, the top left side presents not a sun or a star, but a small yellow square, suggesting that the work may be not so much a fanciful interpretation of the sky but a visual language that requires further decoding. Strong diagonals originating below the square lead the eye down to blurred, arrowlike marks at the bottom right. These hazy forms in turn serve as transitions between the central field and the inky starbursts at the right and throughout the border. Klee's use of wet-on-wet technique in both the center and the periphery of the composition encourages the viewer to consider the sandy orange border at the right and left and the thin washes of ink at the top and bottom not as a mere framing device, but rather as an integral aspect of the carpetlike composition. Klee's varied application of watercolor, which ranges from the crisply painted forms in the very center to the blotting of the modulated yellow background and the seeping of the black wash into the yellow at the top and bottom, serves an important purpose in addition to providing visual interest. It asserts that this is in fact a painting despite the allusions to written language and to the applied arts. In other words, one would never mistake this watercolor for a clay tablet or a carpet. Klee firmly grounds his references to the celestial or the heavenly in the material form of an abstract painting.

The artist's interest in the ways various artistic media could enrich painting, exemplified in Collection of Southern Signs in its allusions to Cunieform script and to Oriental carpets, and in the relationship between the material and the spiritual in abstract art, developed in the context of the Blue Rider artist's group in Munich, which Klee joined just after its founding in late 1911. These artists, whose members included Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, thought that academic art grounded in classical antique and Renaissance tradition had become too regulated and sterile, leaving no room for personal expression. Although they largely abandoned idealized religious subject matter, which had heretofore been represented as realistic scenes composed according to one-point linear perspective, they thought that art should still facilitate contemplation of the spiritual or the intangible. They therefore turned to non-Western objects like masks, carvings, and textiles—which they believed conveyed a sense of the otherworldly—as models for their own abstract art.

The artists who founded the Blue Rider in 1911 had become familiar with the arts of the so-called Orient at the 1910 Munich exhibition, Masterpieces of Mohammedean Art. It was there that they saw Persian miniatures, which often combine text and image, and Oriental textiles and carpets displayed against white gallery walls, as if they were modern European art. Kandinsky's and Marc's writings of 1910 indicate that they thought these works achieved what they themselves hoped to in their own abstract painting.3 As Klee scholar Michael Baumgartner has surmised, it is unlikely that Klee attended the famous exhibition, as he was in Switzerland for most of its duration, but his enthusiastic colleagues most likely told him about it later.4 Significantly August Macke, prior to his 1914 trip to Tunisia with Klee and Louis Moilliet, had made several works inspired by "Oriental" textiles after seeing the exhibition.5 In Tunisia, both Klee and Macke painted works inspired by the loose, gridlike compositions of Tunisian textiles.6 While Klee's colleagues may have been inspired by the 1910 exhibition, his own encounter with Islamic and Berber cultural production in Tunisia—including the carpets on display at the bazaars—likely fueled what would become for him a lifelong engagement with "Oriental" and non-Western art.

Over the course of the decade between the Tunisian journey of 1914 and making Collection of Southern Signs in 1924, Klee alluded to Tunisia or to the "Orient" in the titles of many of his paintings, such as In the Style of Kairouan (1914), which refers to a city he visited in Tunisia, Oriental Experience (1914), Moonrise in St. Germain (Tunis) (1915), and View from St. Germain (Tunis), Looking Inland (1918). What is more, even as he continually returned to his earlier Tunisian watercolors and his memories of that exotic journey for subject matter, Klee also began to draw widely from various forms of non-Western artistic production, including poetry. A poet himself, in 1916 Klee began a series of painted poems entitled Chinese Poems that were inspired by German translations of Chinese poetry.7 And in 1917, he painted the miniature-like Persian Nightingales, which scholars agree was inspired by the verses of the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafiz, whose writings the artist likely knew in translation.8

Klee's investigation of the ways various artistic media could inform painting intensified during his ten-year tenure as a professor at the Bauhaus from 1921 1931. His job there was not only to teach students of the applied arts the basics of composition and color, but also to make art himself that could inspire his pupils' designs. During the mid- to late-1920s, he had an especially fruitful artistic exchange with those of his students who specialized in weaving. As T'ai Smith argues in the 2009 Bauhaus: Workshops of Modernity exhibition catalog, the weavers learned from their professor's attempts to improvise within a given structure.9 For instance, in Collection of Southern Signs, Klee adapts the format of a medallion surrounded by a border common in Oriental carpets, but his allusions to ancient writing and his bold assertion of the material qualities of watercolor painting also bespeak his wider artistic project. This was significant for the weavers who had to work within the limits of the gridlike warp and weft structure of their medium. Klee in turn saw the weavers' task as similar to his own: in 1923 he painted the watercolor In the Style of a Carpet Design, in which he varied colors and forms within a grid. Smith further points out that, just as Klee adapted the forms of ancient writing and the compositions of Oriental carpets, the weavers too turned to non-Western textiles for inspiration.10

In 1924, Klee was likely looking back over his career and the ways travel had influenced it: at that time, the recognized modernist was preparing for his second major retrospective, which would be held at his dealer Hans Goltz's Munich gallery in 1925. Before the fall semester of 1924, Klee journeyed south once again, but this time he stopped just short of North Africa, traveling only as far as Sicily. The reference to the south in Collection of Southern Signs is broad enough to encompass the Tunisian journey of 1914 and this new trip of 1924; the work's desertlike colors could evoke either the Tunisian or the Sicilian landscape. Collection of Southern Signs thus testifies to the artist's initial and expanding interests in unfamiliar places and cultures and the ways they sustained and enriched his work as his professional circumstances changed. That is, it suggests how Klee's journeys south facilitated the metaphorical travel of artistic influences from wide-ranging "Oriental" cultures to his own modern European art.

- 1 Paul Klee, letter to Lily Klee, April 15, 1930, as cited in Marcel Franciscono, "Paul Klees Sizilienurlaub von 1924," in Paul Klee: Reisen in den Süden "Reisefieber praecisiert," ed. Uta Gerlach-Laxner and Ellen Schwinzer (Ostfildern Ruit bei Stuttgart: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1997), 58 (translation mine).

- 2 During the 1910s and 1920s, Klee traveled frequently to Berlin, where he could have seen Cuneiform tablets on display at the Kaiser Friedrich Museum (now in the collection of the Museum of the Ancient Near East at the Pergamon Museum). What remains of the artist's original library, which is housed today at Klee's archive at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland, suggests that the artist had some interest in the ancient Near East. He owned Georg E. Burckhardt's 1916 German translation of Gilgamesh, the ancient epic poem that survived in the form of Cunieform tablets. Later, he acquired the 1926 edition of Carl Bezold's Ninive und Babylon. The latter had been in print since 1903 and included photographs of clay tablets with Cunieform writing.

- 3 See, for example, Kandinsky's laudatory review of the 1910 exhibition: Wassily Kandinsky, "Brief aus München V," Apollon 11 (October / November 1910): 1317, reprinted in Wassily Kandinsky: Gesammelte Schriften 1889-1916, ed. Helmut Friedel, trans. Jelena Hahl-Fontaine (Munich: Prestel, 2007), 369-73. Franz Marc later compared Kandinsky's abstract paintings to the Oriental carpets on display at the 1910 exhibition, claiming that both challenge traditional European concepts of painting. See Franz Marc, "Zur Ausstellung der `Neuen Künstlervereinigung' bei Thannhauser," in Franz Marc: Schriften, ed. Klaus Lankheit (Cologne: DuMont, 1978), 126-27.

- 4 Michael Baumgartner, "Paul Klee und der Mythos vom Orient," Auf der Suche nach dem Orient, ed. Michael Baumgartner and Carole Haensler (Bern: Zentrum Paul Klee; Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2009), 137.

- 5 On August Macke's Orientalist paintings from before 1914, see Ernst-Gerhard Güse, "Vor der Tunisreise," in Die Tunisreise: Klee, Macke, Moilliet, ed. Ernst-Gerhard Güse (Stuttgart: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1982), 2327.

- 6 The artists' third traveling companion, Louis Moilliet, later recalled how Macke painted Vendor with Jugs (1914) in the style of a Tunisian textile. See Moilliet as told to Walter Holzhausen, "The Visit to Tunisia," in August Macke, Günther Busch, and Walter Holzhausen, August Macke: Tunisian Watercolors and Drawings, trans. Norbert Guterman (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1959), 19. For more on Klee and Tunisian textiles, see my forthcoming essay, "`The Carpet-like Aspect in his Representations': Paul Klee's Tunisian Watercolors in Context," in Der Künstler in der Fremde. Wanderschaft-Migration-Exil. Vorträge aus dem Warburg-Haus, ed. Uwe Fleckner (Berlin: Akademie Verlag).

- 7 For an in-depth analysis of Klee's most famous work from the series Chinese Poems, "Once emerged from the gray of the night..." (1918), see Joseph Leo Koerner, "Paul Klee and the Image of the Book," in Rainer Crone and Joseph Leo Koerner, Paul Klee: Legends of the Sign (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 55-65.

- 8 For example, Wolfgang Kersten and Osamu Okuda cite Hafiz's poetry as an important reference for Persian Nightingales in "Vogelkunde, Vogelbilder, 1917-1923," in Paul Klee: Im Zeichen der Teilung, die Geschichte zerschnittener Kunst Paul Klees (Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 1995), 66-67. On Klee's likely familiarity with Persian poetry, see Baumgartner, "Paul Klee und der Mythos vom Orient," 135.

- 9 T'ai Smith, "Unknown Weaver, Possibly Else Möge, Wall Hanging, 1923," in Bauhaus: Workshops of Modernity, ed. Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 116.

- 10 Ibid., 119.