Odilon Redon, Une femme revêtue du soleil (A Woman Clothed in Sunshine), 1899

Orin Zahra

PhD student, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Washington University in St. Louis

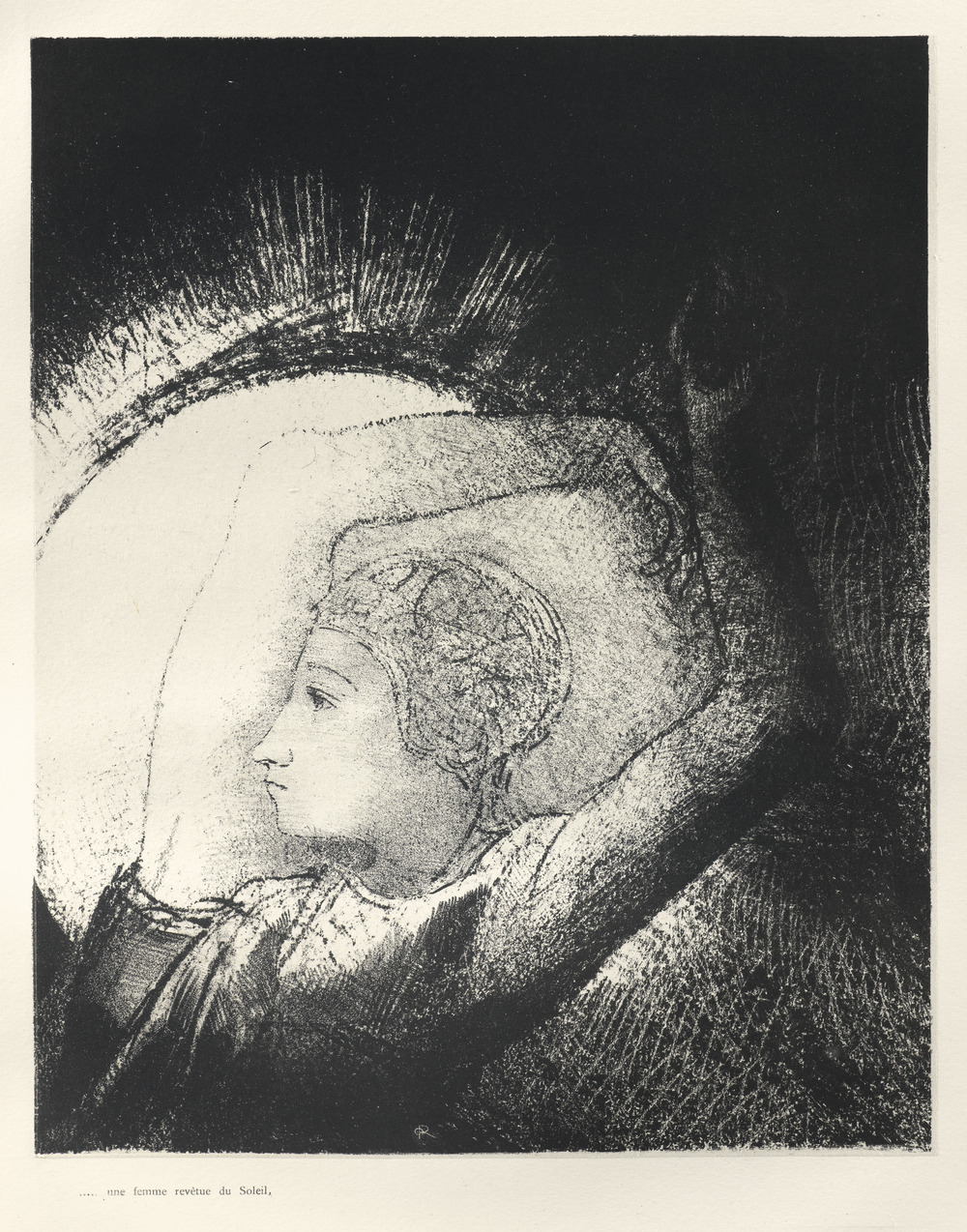

Odilon Redon’s Une femme revêtue du soleil captivates the viewer with its rendering of an enigmatic woman, her arms elevated and fingers gently curled in the stance of a graceful ballerina. She is seen in profile, silhouetted against an incandescent orb that emits dazzling sparks of light. Her dress and cap suggest that she is not supernatural but a woman of the corporeal world. Yet her dreamy, inexpressive face and the rendering of her lower body, cut off from the viewer and consumed by shadow, imbue her with an ethereal spirit. With no other indications of her surroundings or identity, she exists within and is defined solely by this nebulous realm of light and darkness.

This print is the sixth of twelve plates from Redon’s final lithographic series, an album of images illustrating the Apocalypse of Saint John, the last and only prophetic book of the New Testament, also known as the book of Revelation.1 Redon’s twelve plates correspond to different sections of the biblical text, and the captions below each image are quotations taken from the book in sequential order. The caption “une femme revêtue du soleil” refers to chapter 12, in which a heavenly figure described as “a woman clothed with the sun” is set in a cosmic battle against a fire-breathing dragon.2 Redon’s print provides us with none of the details needed to place this woman within this biblical allegory, and the composition’s setting is so abstract that the original religious context would be undetectable were it not for the inclusion of the caption. The artist deliberately complicates any simple understanding of the work by shrouding the image in an aura of ambiguity.

Redon’s embrace of the ambiguous and idiosyncratic was symptomatic of the Symbolist movement prevalent at the time, which arose in the 1880s as a reaction against artistic representations of an objective and rational real world, advocating instead for art to express abstract ideas, the imagination, and subjectivity.3 Symbolist artists frequently explored opposites or dualities, such as the fantastic and the real, good and evil, light and dark, as exemplified in this print. While Redon’s interpretation of the apocalyptic allegory appears tame in comparison to the rest of his work—much of which includes mutilated, distorted, and fused bodies of humans, animals, plants, and inanimate objects—Une femme revêtue du soleil still bespeaks Symbolist sensibilities, particularly the desire to evoke something felt rather than to describe something tangibly seen. Instead of using traditional iconography to visualize the allegory, Redon invokes a vision of a celestial being, albeit an earthly woman’s face, whose purity is alluded to through penetrating light contrasting with opaque darkness.

The sense of ambiguity comes not only from the content—the allusive subject matter—but also from the form, in particular the multitextured surface created through the lithographic medium. The combination of halo-like light and dense black areas may allude to the battle between the woman and the dragon or perhaps to the conventional depiction of the woman bathed by the sun with a crown on her head. But the composition also consists of gradations of gray, seen especially on the lower right edge, overtaking the woman’s left arm and parts of her head. This shading invokes a liminal space, one that is not determined by such binaries as good or light versus evil or dark but rather recalls the Symbolist emphasis on ambiguity and mystery.

Between 1878 and 1900 Redon produced close to thirty etchings and 170 lithographs that were conceived in part as a way to publicize his richly textured, often cryptic charcoal drawings, which he termed noirs.4 The noirs exemplify Redon’s fascination with the impact and resonance of black.5 As with this lithograph, he printed almost exclusively using chine appliqué, a type of print in which an impression is made on a thin sheet, backed by a stronger, thicker wove paper to which the image is transferred using a press. Through both the subtle range of colors offered by the chine appliqué and his use of the lithographic crayon, Redon’s primary tool for making prints, the artist was able to achieve intense and nuanced effects of hues and contrasts of light and dark. In Une femme revêtue du soleil, it is precisely because of the density of the black spaces that the lighter surrounding areas appear to glow, demonstrating the artist’s exceptional understanding of the potential effects of black in a lithograph.

Redon’s prolific production of lithographs was part of a larger nineteenth-century print revival, championed by Ambroise Vollard, the prominent art dealer who commissioned and published Redon’s Apocalypse of Saint John. At the turn of the century, apocalyptic visions in literature and art were common, a reflection of a broader societal anxiety, the belief that the end of civilization was imminent.6 As Starr Figura contends, the choice to publish this album in 1899, the year many feared would usher in the end of the world, suggests that Vollard as well as Redon may have been trying to capitalize on these widespread anxieties.7 In the same year Sigmund Freud published his Interpretation of Dreams, which explores how human impulses and desires are released through dreams and the unconscious, certainly congruent with Symbolist ideas. The works of Freud and fellow psychiatrist Carl Jung were highly influential for Symbolists, and concurrently Freud once described Redon as a man who “molds his phantasies into new kinds of realities, which are accepted by people as valuable likenesses of reality.”8 Thus, in connecting the prophecy from the book of Revelation to the very real fin-de-siècle fears of an actual Armageddon, Redon established a new imagined reality. Though born from his fantasy, the imagery in this album would surely have resonated with those who were consumed by such forebodings.

These apocalyptic fears correspond to a turn to spirituality, which was a major component of Symbolism that contested the secularism of the government under the Third Republic.9 Some artists, such as Maurice Denis, focused on Catholicism for inspiration, while others, such as Redon and Gustave Moreau, were deeply interested in mysticism, invoking imagery not only from Christianity but also from Buddhism, Hinduism, and other Eastern philosophies. In earlier works Redon had used the motif of the isolated head in multiple religious and cultural contexts. The Golden Cell (1892) and Sita (1893), for example, feature this motif and refer to Hindu mythology and Buddhist concepts of the origins of the universe. Another print, The Druidess (1891), shows the enigmatic profile bust of a Celtic priestess; in Redon’s time the Celts widely represented irrational and primitive power, in contrast to the instrumental reason and rationality of their Roman conquerors.10 Symbolists such as Redon and Moreau often focused on images of the eye and the head, the principal sites of contemplation and awakening. With her arms outstretched, her head outlined against the light, and her expression suggesting introspection, it appears as if the woman in Une femme revêtue du soleil is emerging out of the darkness into a state of spiritual awakening. The connections to other belief systems add layers of meaning beyond the Christian revelation itself, but as in much of Rodin’s work, these references are elusive.

And yet for all its spiritual connotations, Une femme revêtue du soleil is simultaneously secular, a point that becomes clearer when it is compared with various precedents. In Albrecht Dürer’s influential series of fifteen woodcuts, also titled Apocalypse of Saint John (1498), the artist filled the scene with a profusion of details—angels, God, a distinct landscape, and the evil dragon as a clear foil to the holy woman. More than a hundred years later, Diego Velázquez’s companion pieces painted in 1618, St. John the Evangelist on the Island of Patmos and The Immaculate Conception, feature the traditional religious iconography of the moon at the woman’s feet and a crown of stars above her head, in celebration of the 1617 papal decree defending Marian dogma.11 In contrast to these earlier variations, with the exception of the radiating lines also seen in Dürer’s woodcut, Redon stripped his composition of overt religious imagery, dramatically simplifying the image to focus solely on the woman. And although the album may have been intended to tap into the apocalyptic fascinations of its time, unlike Velasquez’s paintings, it was not commissioned for a religious occasion.

Redon was not the only artist to leave the viewer with questions regarding the meaning of the subject. William Blake’s painting The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun (1803–5) shows a monstrous anthropomorphic dragon with wings, horns, and human legs standing over a reclining woman with long, flowing golden hair, the connection between the two adversaries oddly sensual. Although he strays from the traditional representations of the dragon and Marian figure, Blake, too, subtly includes the moon and stars, providing clues to the woman’s identity. Furthermore, though her arms are raised like those of Redon’s figure, her hands appear to be together in prayer. There are no such recognizable markers of ritual in Redon’s lithograph; rather, his Virgin Mary can even be read as a type of stage performer along the lines of Loïe Fuller.12 The ambiguity in Blake’s painting is a result of reworking the allegory into a romanticized mythological drama between the woman and the dragon, while the equivocal nature of Redon’s print comes from the near exclusion of religious references, thereby conflating the sacred with the profane.

In Une femme revêtue du soleil, form complements content; the indeterminate dark, light, and shadowy gray spaces created by the lithograph perfectly suited the Symbolist desire to render a deeply evocative image. Musing in his diary in 1888 about those who view his prints, Redon wrote, “What have I put into my work to suggest so many subtleties to them? I placed a little door opening on mystery. I have made fictions. It is for them to go further.”13 Indeed, Redon’s seemingly simple composition refers to the biblical vision of the Apocalypse of Saint John, hints very broadly at other spiritual beliefs, simultaneously presents a secular image through the absence of a fully developed traditional religious iconography, and can be seen as echoing fin-de-siècle apocalyptic fears. He leaves it to the viewer’s imagination to arrive at a conclusion, but perhaps above all Redon’s lithograph signifies the Symbolist belief in the subjectivity of art and the impossibility of fixed meaning.

- 1 Redon executed an extraordinary number of lithographic albums over a period of twenty years and was already transitioning to color works at the time he created the Apocalypse of Saint John; this was his last album in the lithographic medium before he shifted over fully to pastels and oils. See Francis Carey, ed., The Apocalypse and the Shape of Things to Come (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 297.

- 2 The book of Revelation contains apocalyptic warnings to Christians about the consequences of straying from their faith through a series of allegories. The woman in Revelation 12 is about to give birth to a powerful child while being pursued by an enormous red dragon. The child is swept up to God as the woman flees into the desert for safety. The woman is commonly interpreted as the Virgin Mary, the dragon as Satan, and the child as Christ with allusions to his inevitable resurrection. Traditionally the woman is depicted standing on the moon wearing a crown of twelve stars, and the dragon has seven heads, ten horns, and a crown on each head. See Natasha O’Hear and Anthony O’Hear, Picturing the Apocalypse: The Book of Revelation in the Arts over Two Millennia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 110–12.

- 3 See Michelle Facos, Symbolist Art in Context (Oakland: University of California Press, 2009), 14.

- 4 See Starr Figura, “Redon and the Lithographed Portfolio,” in Beyond the Visible: The Art of Odilon Redon, ed. Jodi Hauptman (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2005), 77.

- 5 Interest in the color black in the latter half of the nineteenth century had preludes in the earlier part of the century, namely, the dark Romanticism of such artists as William Blake, Eugène Delacroix, and Francisco de Goya, whose art evokes a dark, savage, irrational world in the midst of turbulent times. See Lee Hendrix, ed., Noir: The Romance of Black in 19th-Century French Drawings and Prints (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015), 17–19.

- 6 Examples include H. G. Wells’s novel The War of the Worlds (1897), which symbolizes changes to traditional life caused by technological advancements in Western society, and Auguste Rodin’s monumental sculpture The Gates of Hell (1880–1917), which reflects the immorality of modern society and its consequences through a depiction of forbidden love, sexuality, and suffering. Edvard Munch similarly explored the intense alienation and melancholy of the modern individual in such works as The Scream (1893) and Anxiety (1894). Redon’s color lithograph was published in Vollard’s 1896 Album des peintres-graveurs. See Phillip Dennis Cate, Gale B. Murray, and Richard Thomson, Prints Abound: Paris in the 1890s; From the Collections of Virginia and Ira Jackson and the National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2000), 23.

- 7 Figura, “Redon and the Lithographed Portfolio,” 93.

- 8 Sigmund Freud, quoted in Alfred Werner, introduction to The Graphic Works of Odilon Redon (London: Dover, 1969), xiii. Jung was also interested in Redon’s work, which he likely encountered in Paris; he owned a catalog of Redon’s graphic works as well as a study of the artist. See Sonu Shamdasani, “Liber Novus: The ‘Red Book’ of C. G. Jung,” in C. G. Jung, The Red Book: A Reader’s Edition, ed. Sonu Shamdasani, trans. Mark Kyburz, John Peck, and Sonu Shamdasani (New York: Norton, 2009), 33–34.

- 9 The political philosophy of the Third Republic, established in 1871, after the Franco-Prussian War, was based on democratic and egalitarian principles of French republicanism. This secular form of government caused friction with opposition groups, including the Roman Catholic Church, dividing all classes on either side of the conflict. From these circumstances of church versus state arose both anticlerical artists and a Catholic and religious revival in the arts, as seen particularly in the work of the Symbolists. See Facos, Symbolist Art in Context, 95–96.

- 10 Dario Gamboni, “Parsifal / Druidess: Unfolding a Lithographic Metamorphosis by Odilon Redon,” Art Bulletin 89, no. 4 (2007): 773.

- 11 O’Hear and O’Hear, Picturing the Apocalypse, 125. In Marian dogma the “woman clothed with the sun” signifies the immaculate conception of Mary and the pure, privileged state of her body in which the Church places hope for salvation. See Timothy Verden, Mary in Western Art (New York: Hudson Hills, 2005), 53–55.

- 12 Loïe Fuller was a highly popular American performer at the turn of the century, famous for her visually spectacular skirt dancing and luminescent lighting on stage. The light behind Redon’s female figure makes a particularly convincing connection with Fuller’s trademark use of light during her performances. See O’Hear and O’Hear, Picturing the Apocalypse, 127.

- 13 Redon, quoted and translated in Robert Goldwater, Symbolism (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1980), 116.