Wolfgang Tillmans, Portrait series, 2001

Anna Warbelow

PhD candidate, Department of Art History & Archaeology, Washington University in St. Louis

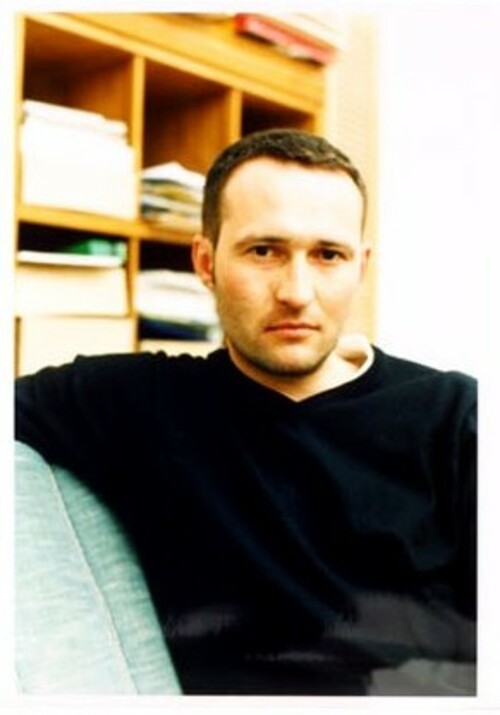

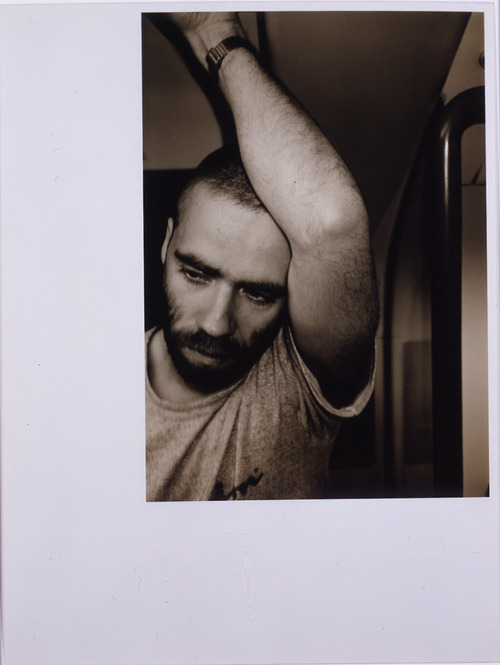

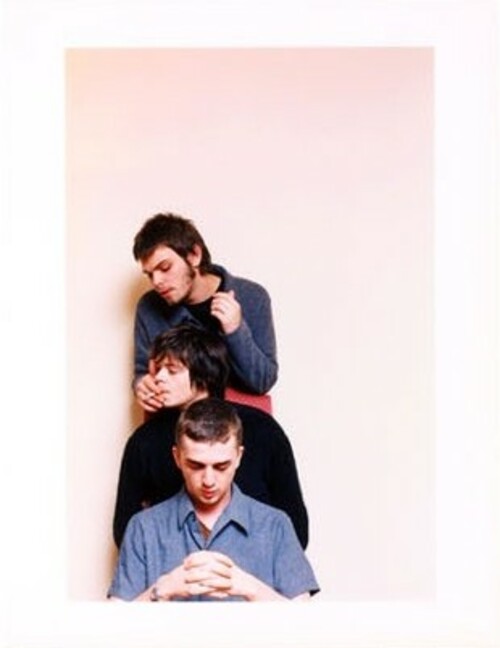

Throughout his oeuvre German artist Wolfgang Tillmans has grouped his varied subjects and compositions into four broad categories: still lifes, landscapes, abstractions, and portraits. Tillmans experiments with these traditional genres of art history, expanding the definition of what constitutes each and often blurring the distinctions between them. He most consistently returns to the genre of portraiture, and in 2001 he compiled a portfolio of fifteen works from his Portrait series, in which he photographed a variety of people, including friends, family, celebrities, and strangers, with an ever-shifting style. Considered as much an installation artist as a photographer, Tillmans often presents his portraits in groupings tacked to the gallery wall or laid out on display tables and mixed with images from his other series as well as from popular media such as newspaper clippings and magazine spreads. His photographs are rarely shown singularly as autonomous art objects, a tendency that seems to be supported by Tillmans’s claim that he is “interested not in individual readings, but in constructing networks of images and meanings capable of reflecting the complexity of the subject.”1 Each portrait when read closely participates in a web of contextual meaning drawn from sources including art history, the mass media, Tillmans’s other works, and his personal life. Through a close look at three photographs from this portfolio, Su Khedev Reel (2000), Alex (1997), and Paula, typewriter, looking (1994), this essay explores the way this web of context creates meaning for individual portraits and works to expand standard definitions of portraiture.

The fifteen photographs in this portfolio were framed by Tillmans in simple light wood frames, without matting, and are in many instances off-center. While Tillmans often produces large inkjet prints, which he attaches directly to gallery walls with binder clips or tape, he began incorporating framed C-prints into his installations in 2000. Russell Ferguson suggests that Tillmans “has consistently pushed back against whatever preconceptions of his work seem most current,” causing the artist to constantly alter his approach.2 A display comprised only of these framed C-prints appears more conventional at first glance and rather far from the installation work for which he has become known; however, Tillmans still presents the portraits as part of a series, which invites readings across the frames. While this kind of installation does not include newspaper and magazine clippings, these sources still provide much of the framework for understanding the portraits—only now, the viewer must look beyond the gallery walls.

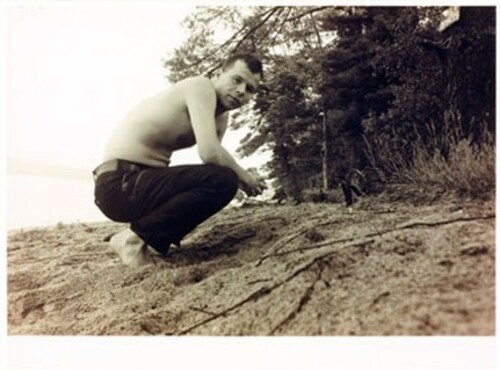

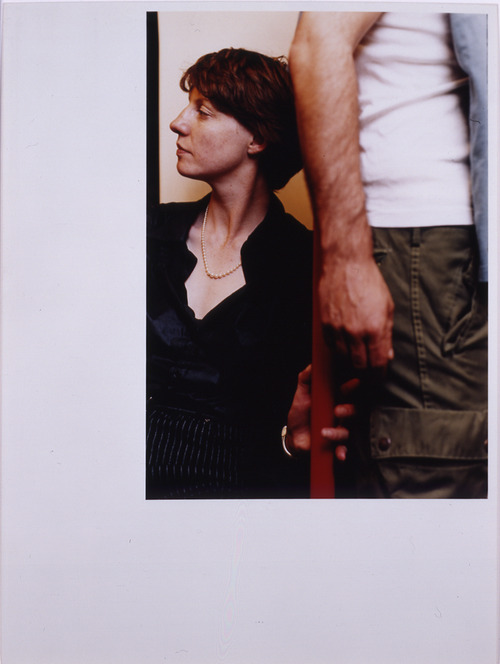

In his portrait of Su Khedev Reel from 2000, Tillmans draws mainly from the mass media, particularly sensationalist news sources to create a multifaceted portrait that hauntingly pulls the viewer into the subject’s tragic story, but also allows the viewer to consider the various uses for photographic portraiture—from identification, police surveillance, and photographic journalism, to remembrance and mourning. Just right of center, a middle-aged woman stares blankly at the camera, her hand resting on an imposing bright blue couch, which oddly divides the composition. A large photograph of a young man hangs behind her head, acting as the second figure in this double portrait. The layered composition points to the complexity of the subject’s story and the layers of context needed to take meaning from this photograph.

Tillmans began collecting newspaper articles and photographs as a child and later collected entire newspapers covering stories that captured his curiosity. The Reels’ story may have been of particular interest to him because of the significant role photography plays in it, which he references in his portrait. By 2000 Sukhdev Reel was a household name in London, where her face and her story appeared in newspapers and on television as she spoke out against the hate crime committed against her son: in October 1997 twenty-year-old Ricky Reel was allegedly attacked and beaten to death by two white youths. Tabloids spread the story, and public protests were staged in support of the Reel’s claim that the police had failed to properly investigate their son’s murder. Headlines such as “Parents Demand Justice for Model Son” spun a story of violent racial tension, police indifference and corruption, and the loss of an innocent youth.3 Such reports also repeatedly pointed to the role of photography in the affecting story. When Ricky did not return home, his friends and family searched for him by handing out photographs of him— documentation of his physical appearance. The family also worked to collect security camera footage, turning to the assumed veracity of the captured images to solve their son’s murder. According to the British Guardian, long after Ricky’s death, photography continues to serve an important function for Sukhdev: each night she reportedly puts a photograph of her son to bed and wakes it up in the morning.4 The photograph has effectively become a placeholder, a fetish, a memory keeper. The framed photograph behind Reel in Tillmans’s portrait may be the same one passed around by his friends and family or the one Sukhdev tucks in each night; Tillmans allows such details to serve many functions, revealing the complexity of both the subject and his own interest in the story.

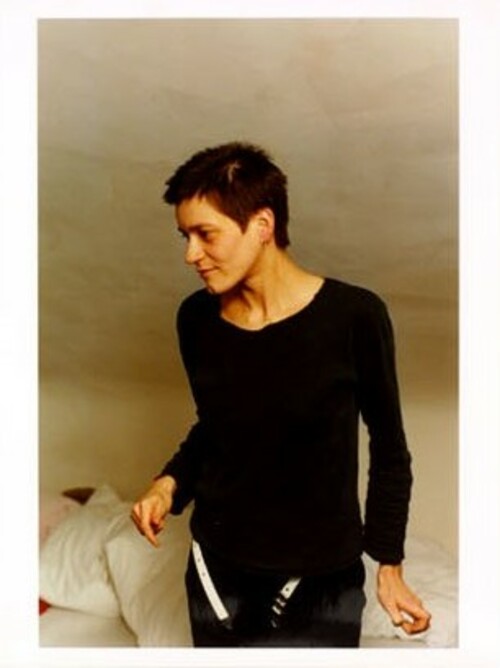

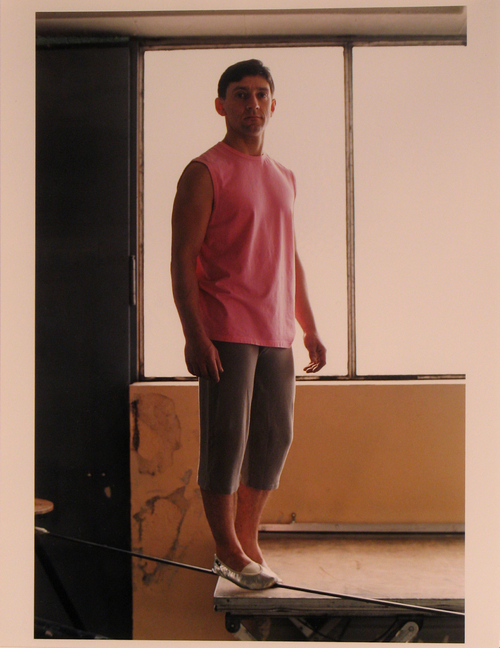

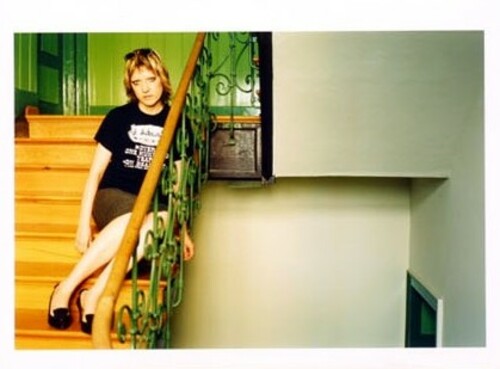

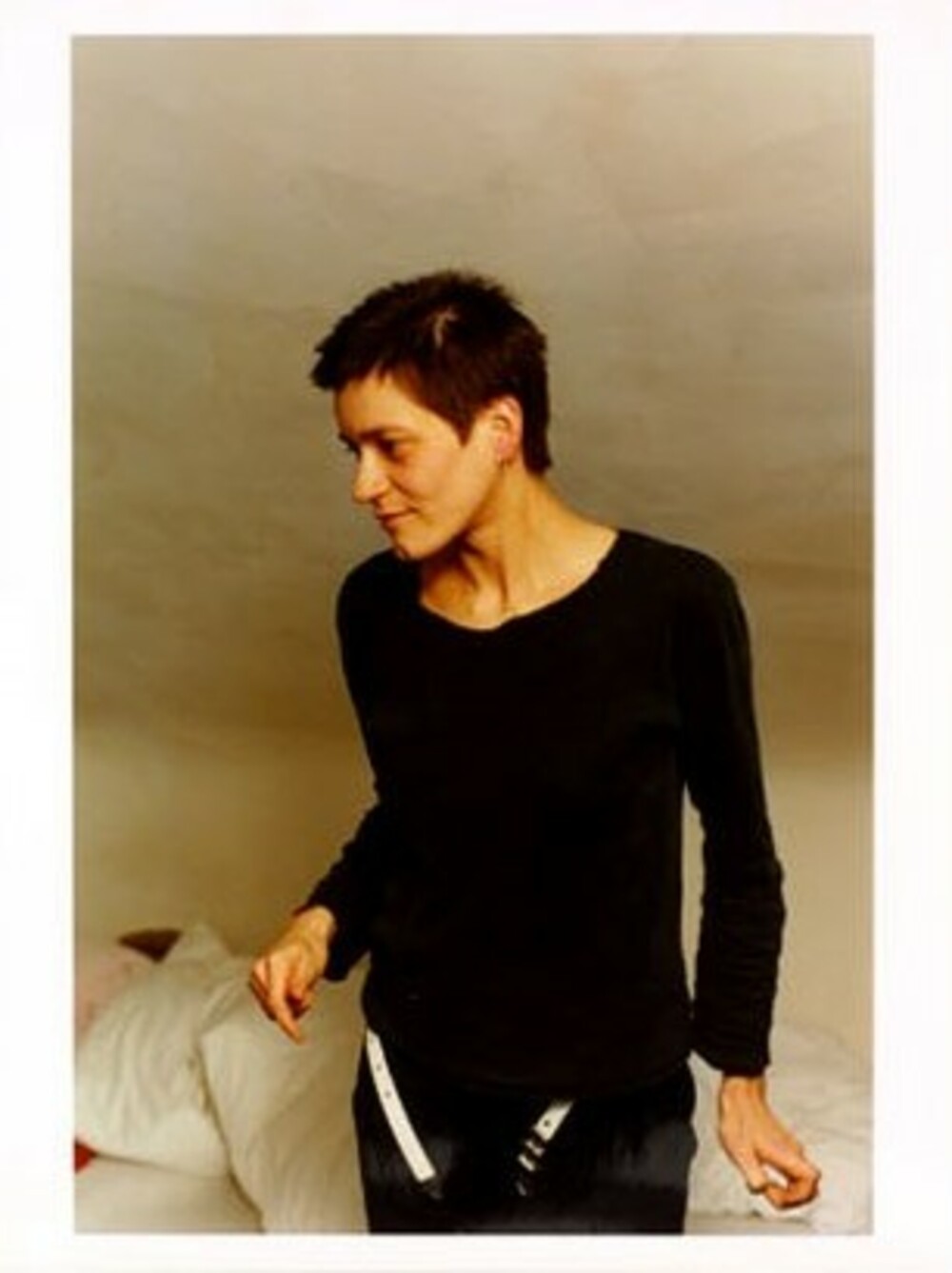

As a young gay artist, Tillmans has repeatedly pointed a camera at his friends and their daily activities to create portraits that explore gay youth and club culture in Britain and Germany. Alex (1997) appears to be a candid and intimate snapshot of one of Tillmans’s friends caught midaction in a familiar setting. Yet, the smooth white background, which sets up a stark contrast with the all-black silhouette of Alex, belies the apparent effortlessness of this image and draws on the aesthetics of fashion photography. While Tillmans never actually worked as a fashion photographer, he did photograph celebrities and models, and his photographs have been published in such fashion magazines as Vogue and i-D Magazine, a British publication focused on fashion, music, art, and youth culture.

Alex appears as subject in many of the i-D photographs as well as in several other portraits taken throughout Tillmans’s career. In this particular photograph, the subject’s short-cropped hair and slender body, flattened by her black clothes, make her appear androgynous. The fact that she stands, belt undone, in front of rumpled bedding adds a sexualized undertone to the image as well. This subversion of the gender binary and exploration of sexuality are presented in a rather banal way, and thus normalized. Tillmans’s work follows a generation of artists interested in photography as a tool for exploring the postmodern concept that identity, particularly gender identity, is never stable, singular, or inherent, but rather is socially constructed and fluidly performed.5 When examined alone, Alex posits gender as ambiguous, but when viewed as part of a series of portraits, and as one of many portraits of Alex, this photograph works to suggest the fluidity of gender identity. While here Alex sports more masculine clothing and a short haircut with little of her body exposed, in other portraits she appears nude with breasts bared, and in still others she has longer hair and wears skirts or dresses, all conventional markers of femininity. Drawing together these contextual strands of gender theory, the work of earlier photographers, Tillmans’s personal life, and other images of Alex deepens the reading of this deceptively simple portrait.

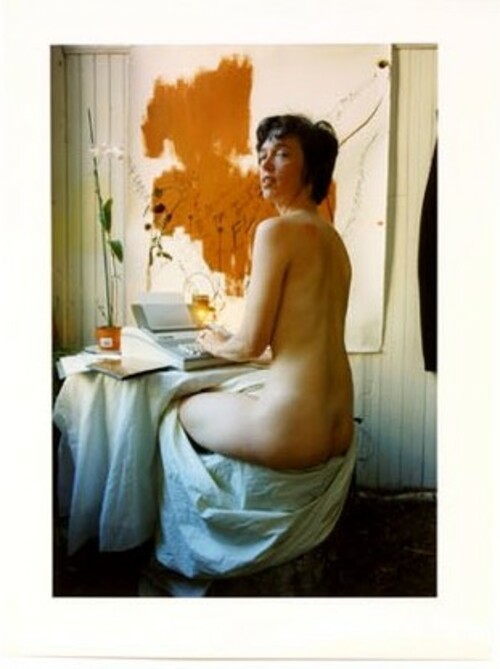

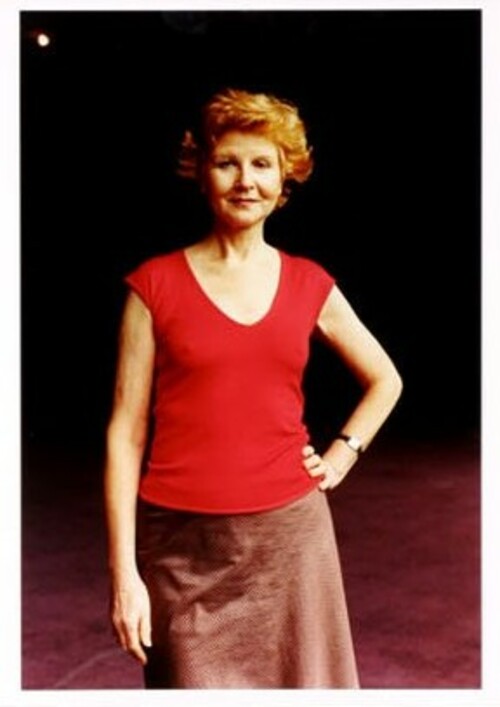

In contrast to the informal appearance of Alex, Paula, typewriter, looking (1994) is the most overtly staged photograph from the portfolio. Here Tillmans alludes to portrayals of the nude woman, not only in mass media, fashion, and street culture, but also in the traditions of high art. Paula’s nude body, seen from behind, draped loosely with a sheet settling around her waist, immediately recalls several famous nudes from art history, including those painted by Rubens and Ingres.6 The photograph also makes a visual nod to famous modernist photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s 1889 portrait of his wife, Paula, Berlin. Tillmans clearly calls on the trope of the nude woman at her bath or the courtesan in her bed. Like many contemporary appropriations, particularly those addressing issues of gender, the photograph might be read as a reiteration of this trope and a perpetuation of art’s objectification of women. Yet a larger contextualization complicates this reading of the portrait.

Like Alex, Paula is one of Tillmans’s close friends and a frequent subject in his work. Tillmans took several photographs of Paula in varying stages of nudity, including some full frontal, as part of a set focused on nudity, in which he also photographed a male friend nude. Tillmans undertook this set because he was interested in what he explained as the “blatant inequality” of female versus male nudity gratuitously used in advertising. He saw his photographs as “challenging the standard formula.”7 This set of nude photographs provides important background for understanding Paula, typewriter, looking and the photograph’s relationship to advertising photography.

Perhaps what is most compelling about Tillmans’s practice is its resistance to a simple explanation of style or subject matter, making each portrait a tool for opening up the genre of portraiture rather than defining it. Readings of these three portraits as part of the fifteen-work set, as part of the Portrait series, as part of Tillmans’s oeuvre, and as part of a much large collection of circulating imagery drawn from such varied sources as art history, news photography, advertising, and fashion photography allows for a richer understanding of the subject and of his practice. Yet, Tillmans’s approach to portraiture remains undefined and experimental, and the individual portraits belie simple or singular meaning. Instead, each portrait, informed by the framework the artist provides, begins to reveal additional layers of signification, adding to the multiplicity of interpretations available to Tillmans’s work.

- 1 Quoted in David Deitcher, “Lost and Found,” in Wolfgang Tillmans: Burg (Cologne: Taschen, 1998).

- 2 Russell Ferguson, “Faces in the Crowd,” in Julie Ault et al., Wolfgang Tillmans (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), 65.

- 3 For an example of this kind of reporting on the incident, see Vikram Dodd, “Parents Demand Justice for Model Son,” The Guardian, November 9, 1999, http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/1999/nov/09/race.world1.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 For a theoretical discussion of postmodern gender identity, see Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1999). For examples of postmodern photographers interested in gender performance, see Jennifer Blessing and Judith Halberstam, Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: Gender Performance in Photography (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1997).

- 6 See, for example, Peter Paul Rubens, Venus at the Mirror (c. 1615) and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Bather of Valpincon (c. 1808).

- 7 Wolfgang Tillmans, “Challenging the Standard Formula: Wolfgang Tillmans,” The Guardian, April 19, 2004.